Hillside Construction

Building on Los Angeles terrain requires specialized knowledge - from access logistics and site retention through structural coordination with the slope.

Hillside construction in Los Angeles is not a harder version of flat-lot construction. It is a fundamentally different discipline - different engineering, different equipment, different regulatory framework, different coordination requirements, and a different risk profile. Every design decision on a hillside site cascades through permitting, foundation engineering, grading operations, and construction logistics in ways that don't exist on level ground.

This page covers what hillside construction actually involves: the site conditions that drive cost and complexity, the regulatory framework that governs what you can build and how you can build it, the foundation and grading operations that account for the majority of the budget premium, and the coordination required to manage it all. It's written from the perspective of someone who manages these projects - not someone who markets them.

Last updated: February 2026

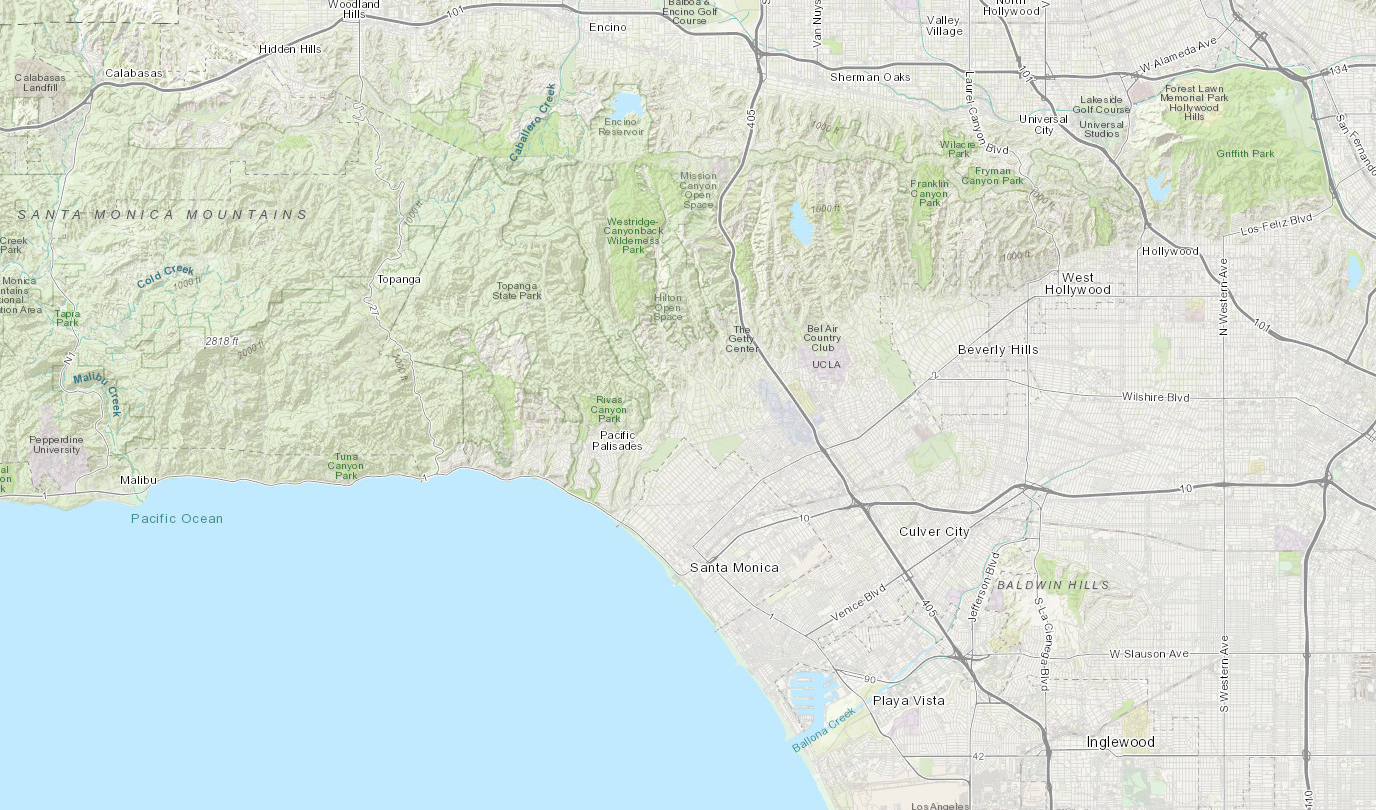

Understanding Hillside Sites

Before discussing what you build on a hillside, you need to understand what you're building on. The site conditions - slope, soil, groundwater, fill history - determine the foundation system, the grading strategy, the equipment plan, and ultimately the cost. On a flat lot, site conditions are usually predictable. On a hillside, they're the single largest variable in the project.

What the Slope Creates

Gradient isn't just a number on a topographic map. It determines what equipment can access the site, what foundation system is required, how much material needs to be moved, and how long the project takes. Two lots on the same street with similar square footage can have completely different construction costs based on slope alone.

At 15-20% slope, conventional equipment can typically reach the building pad, grading operations are manageable, and standard foundation systems may work depending on soil conditions. At 30-40% slope, equipment access becomes the primary constraint - you're cutting access roads into the hillside with excavators, working with skid steers and bobcats in tight conditions, and the foundation system almost certainly requires caissons or piles drilled to bedrock. Beyond 45% slope, you're in territory where the site development alone - before any structure goes up - can exceed the cost of the house itself.

An excavator can work on steep terrain and cut pathways where you need them, but access is tight and the logistics compound at every stage: material deliveries, concrete trucks, crane positioning, even where your workers park. The slope doesn't just affect the foundation - it affects every trade, every delivery, and every day of the schedule.

Geology and Soil Conditions

LA's hillside communities sit on a range of geological formations, and the subsurface conditions vary dramatically - sometimes across a single property. What's under the surface determines everything about the foundation, and you often don't know the full picture until you're in the ground.

The conditions that drive hillside construction decisions in Los Angeles generally fall into several categories:

- Bedrock (sandstone, shale, conglomerate): Generally provides good bearing capacity, but depth varies. Bedrock at 12 feet on one side of a property and 25 feet on the other is common. The difference between weathered rock (which may not meet bearing requirements) and competent bedrock is a distinction that matters enormously during construction and can only be confirmed by the geotechnical engineer in the field.

- Alluvium: Deposited material of variable quality. Can provide adequate bearing in some conditions but requires careful evaluation. Often interlayered with less competent material.

- Expansive clay: Soils with an Expansion Index above 50 require special foundation design to accommodate volume changes with moisture content. Common in many LA hillside areas and a frequent driver of post-tensioned or deepened foundation systems.

- Colluvium: Slope wash material - loose, unconsolidated, and generally unsuitable for bearing. Must typically be removed or bypassed with deep foundations.

The Artificial Fill Problem

This is one of the most significant and least discussed issues in LA hillside construction. Fill placed before 1963 is classified as "old fill" under the Los Angeles Municipal Code and is not certified under modern grading code requirements. Its composition is unknown, its compaction is unknown, and its depth is often unknown until you start digging.

Pre-1963 fill cannot be assumed to have any bearing capacity. When it's discovered - whether through geotechnical investigation or during excavation - the response is typically one of two paths: removal and recompaction (R&R), where the uncertified fill is excavated, exported, and replaced with properly compacted certified fill; or deep foundations that bypass the fill entirely and bear on competent material below it.

R&R on a hillside site is a fundamentally different operation than R&R on a flat lot. The excavated material has to go somewhere - which means trucks on narrow hillside streets, haul route approvals, and restricted hauling hours. Certified replacement fill has to come from somewhere - which means sourcing, testing, and importing material on those same constrained streets. Every lift of new fill requires compaction testing and soils engineer observation. And while the excavation is open, the surrounding slope needs to remain stable, which may require temporary shoring that wasn't in the original budget.

Groundwater

Hillside sites frequently have seasonal perched water tables, springs, and seeps that only become apparent when you cut into the slope. Water at the bottom of caisson holes during drilling is common and requires specific responses: casing the hole to prevent collapse, pumping to manage water levels, and switching to tremie pipe concrete placement with higher-PSI mix designs to ensure the concrete displaces the water properly and achieves full structural capacity.

None of this is unusual - it's a standard part of hillside foundation work. But it requires a drilling contractor who has dealt with it before, a soils engineer who can evaluate conditions in real time, and a construction manager who has planned for the possibility and has the right concrete mix and equipment staged. The cost of being prepared for water is minor. The cost of being surprised by it is not.

The Geotechnical Investigation

A standard geotechnical investigation includes 3-4 borings, laboratory testing, and an engineering report with foundation and grading recommendations. On a flat lot, this is usually sufficient. On a hillside site, it often isn't - because soil conditions can change dramatically across short horizontal distances when there's significant elevation change between borings.

Three borings on a sloped lot may all be at different elevations, and each one only tells you what's happening at that specific point. Bedrock depth can change by 10 or more feet between borings that are 20 feet apart horizontally. If the foundation is designed based on three data points and the actual conditions between those points are materially different, you'll discover it during construction - when the cost of responding is 10 to 40 times what additional borings would have cost during design.

During Design

During Construction

Construction vs. Design Discovery

for Geotech Reports in LA

Surveys and Site Documentation

Survey accuracy matters more on hillside sites than anywhere else, and the margin for error is smaller. A 6-inch vertical error on a flat lot is cosmetic - it might affect a finish grade or a curb height. A 6-inch vertical error on a hillside site can mean a grade beam doesn't reach the bedrock elevation it was designed to bear on, which triggers structural redesign in the field.

The NAVD88 datum reference is critical. Surveys, geotechnical boring logs, and structural plans all need to reference the same vertical datum. When they don't - when the surveyor uses one reference point and the geotech uses another - the result is foundation designs based on assumed elevations that don't match what the field crew encounters. This is a coordination issue that should be resolved before the first permit application, not discovered when the drill rig is on site.

Property line accuracy is also more consequential on hillside lots. Retaining walls, shoring systems, and tieback anchors approach or cross property boundaries more frequently on sloped sites than on flat ones. A boundary dispute that would be trivial on level ground can become a construction-stopping event on a hillside when your shoring system is 18 inches from the neighbor's property line.

The Regulatory Framework

Los Angeles has two primary regulatory layers governing hillside construction: the Baseline Hillside Ordinance (BHO) and the Hillside Construction Regulation (HCR) district. The BHO controls what you can build - size, height, grading quantities. The HCR controls how you can build it - working hours, hauling restrictions, operational constraints. Both must be understood before design begins, because they directly affect project scope, schedule, and cost.

Baseline Hillside Ordinance (BHO)

The BHO (Ordinance No. 181,624, effective May 9, 2011) establishes development standards for single-family homes on lots within the City's mapped Hillside Area, covering R1, RE, RS, and RA zones. It determines how much house you can build and how much earth you can move.

What the BHO regulates:

- Floor Area Ratio: Varies by zone and slope band. Steeper lots get less buildable area relative to lot size.

- Height limits: Vary by slope. Measured from existing or finished grade depending on conditions.

- Setback requirements: May be more restrictive than base zoning on hillside lots.

- Maximum Grading Quantities (MGQs): Vary by lot size and slope band. This is often the binding constraint - the ordinance limits how much dirt you can cut, fill, import, or export.

- Import/export limits: Tighter for lots fronting substandard hillside limited streets. If your street frontage is less than 20 feet wide, your grading quantities are further restricted.

- Slope restrictions: New graded slopes cannot be steeper than 2:1 (horizontal to vertical). Grading on existing slopes of 100% or greater triggers additional review.

- Street access requirements: Minimum 20-foot wide roadway, dedication requirements along lot frontage, and Bureau of Engineering Hillside Referral Form process.

You can check whether your property falls within the BHO mapped Hillside Area using the City's ZIMAS or ZoLA platforms. A slope band analysis prepared by a licensed surveyor will be required as part of the permit application to determine your specific MGQ allowances.

Hillside Construction Regulation (HCR) District

The HCR (Ordinance No. 184,827, effective March 22, 2017) is a Supplemental Use District layered on top of the BHO. While the BHO governs what you can build, the HCR governs the operations of how you build it - and for projects in HCR areas, these operational restrictions are often the primary schedule driver.

Where the HCR applies:

- Bel Air - Beverly Crest Community Plan Area

- Bird Streets and Laurel Canyon

- Franklin Canyon, Coldwater Canyon, and Bowmont Hazen

- Northeast Los Angeles Community Plan Area

What the HCR restricts:

| Restriction | Requirement | Practical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum grading | 6,000 cubic yards cumulative per lot | May force foundation systems that minimize grading |

| Import/export (substandard streets) | 75% of by-right maximum | Further limits material movement on narrow streets |

| Construction hours | Mon-Fri: 8 AM - 6 PM Sat: interior work only, 8 AM - 6 PM No work Sundays/holidays |

10-hour days, 5.5 effective days per week maximum |

| Hauling hours | Mon-Fri: 9 AM - 3 PM only No hauling weekends or holidays |

6-hour daily window - the critical schedule constraint |

| Truck staging | Off-site, outside HCR district | Adds time to every truck round-trip |

| Haul route approval | Required for 1,000+ cubic yards of import/export | Public hearing before Board of Building and Safety Commissioners |

| Site Plan Review | Required for houses over 17,500 SF | Additional discretionary review layer |

Multi-Agency Permitting

Hillside projects in Los Angeles don't go through a single permitting agency. They trigger review from multiple departments, each with their own requirements, timelines, and dependencies. Approval from one agency may be required before another will accept your application.

| Agency | What They Review | Hillside-Specific Issues |

|---|---|---|

| LADBS | Building & grading permits, structural plan check, geotech review | Grading permit separate from building permit; geotech approval can be iterative |

| LA City Planning | Zoning, BHO/HCR compliance, discretionary review | Slope band analysis, MGQ verification, HCR compliance |

| Bureau of Engineering | Street classification, dedication, sewer, drainage, haul route conditions | Hillside Referral Form, street adequacy, haul route approval process |

| LAFD | Fire apparatus access, water supply, hydrant distance | Minimum roadway width, turnaround requirements, maximum driveway slope, sprinkler requirements where access is compromised |

| LADOT | Traffic control for hauling operations | Haul route traffic studies, flagging requirements |

| Bureau of Street Services | Street use permits, repair bonds | Pre-construction street condition documentation, damage bonds for heavy hauling |

| LA Sanitation/Watershed | Stormwater compliance, BMPs | SWPPP required for larger grading operations; hillside erosion control more complex |

The critical path through these agencies is not linear, and dependencies between them can add months if not mapped in advance. A grading permit may require Bureau of Engineering clearance, which requires a haul route approval, which requires LADOT review, which requires a traffic study. Each step has its own timeline, and the sequence must be planned as carefully as the construction sequence itself. For detailed permitting information, see Los Angeles Permitting Overview.

Access and Logistics

Access is the constraint that shapes every other decision on a hillside project. The street width determines what trucks can reach the site. The driveway slope determines what equipment can get to the building pad. The available staging area determines how materials are delivered and stored. These aren't details that get figured out during construction - they determine the construction strategy before the first permit is pulled.

Street and Site Access

Many hillside streets in Los Angeles are 16-20 feet wide - barely two lanes, sometimes effectively one. This limits truck size for deliveries, concrete pours, and hauling operations. It affects crane mobilization, drill rig access, and even where construction workers can park without blocking the road. Overhead utility lines and low-hanging branches add vertical clearance constraints to the horizontal ones.

The access assessment isn't just about whether a vehicle can physically fit on the street. It's about whether it can get to the site, operate safely, and leave without shutting down the road for the neighborhood. On some hillside streets, a concrete truck backing into the property blocks both lanes for the duration of the pour. That reality must be planned for - with traffic control, neighbor notification, and permits - not improvised on the day of.

Equipment Selection

On hillside sites, equipment selection is driven by access, not preference. The drill rig you'd use on a flat lot with 40 feet of clear access may not fit on a hillside site with a 12-foot-wide driveway and a 30% grade. The conventional crane you'd normally mobilize may not have adequate outrigger space on a sloped pad. The options narrow quickly, and each constraint affects cost and schedule.

Common equipment adaptations on hillside sites include:

- Excavators cutting access: On steep sites, excavators work first to cut access roads and paths for other equipment. An excavator can work on very steep terrain - effectively on a 1:1 slope - to create the access that everything else depends on. Skid steers and bobcats handle the tighter grading work once paths are established.

- Limited-access drill rigs: Standard rotary drill rigs require relatively flat, stable ground. On constrained hillside sites, smaller limited-access rigs or even hand-drilling with cradalls and buckets may be the only option. Equipment capability vs. site constraints must be matched before bidding, not discovered when the rig arrives.

- Spider cranes: Where conventional cranes can't access or set up safely, spider cranes - compact, self-leveling cranes that can navigate tight spaces and operate on slopes - provide lifting capability at a premium cost. They're slower and have lower capacity than conventional cranes, which affects schedule and structural steel/form sequencing.

- Line pumps vs. boom pumps: When a concrete boom pump can't reach the pour location or can't set up on the available road width, line pumps with hundreds of feet of hose become the alternative. Longer pump lines mean slower pours and potentially more concrete truck staging time.

Crane Pad Preparation

Most hillside residential projects that require crane lifts need a prepared crane pad - a level, compacted surface with adequate bearing capacity for the crane's outriggers. This is not as simple as clearing a flat area. The crane pad must be engineered:

- Bearing capacity: The geotechnical engineer must confirm that the ground under the crane pad can support the concentrated outrigger loads. On fill or loose soil, this may require compaction, over-excavation and recompaction, or crane mats distributing the load across a larger area.

- Outrigger clearance: Full outrigger extension requires specific dimensions that may not be available on a narrow hillside pad. Partial outrigger configurations reduce lifting capacity, which affects what can be lifted and from what radius - directly impacting construction sequencing.

- Pad slope: Cranes have maximum operating slope tolerances (typically 1-2% for most mobile cranes). On a hillside site, achieving a level pad may require significant grading, and the crane pad excavation itself may need temporary shoring on the downhill side.

- Access and egress: The crane needs to get to the pad and leave when the lift is complete. On hillside sites with single-access driveways, the crane mobilization and demobilization sequence must be coordinated with all other site operations.

Grading and Earthwork

On a flat lot, grading is site preparation - a relatively predictable operation that happens before the real work begins. On a hillside, grading is the real work. It's the most expensive, most time-consuming, and most variable phase of the project, and it's the phase where conditions discovered in the field most frequently diverge from what was assumed during design.

Cut, Fill, and Export Operations

Hillside grading involves cutting into the slope to create building pads, access roads, and foundation excavations, and either filling or exporting the excavated material. The ideal scenario - balancing cut and fill on-site so nothing leaves the property - is rarely achievable on steep sites. Most hillside projects have a net export, which means hauling operations.

Export operations on hillside sites require haul route approval (mandatory for 1,000+ cubic yards under the HCR), truck sizing matched to street width and weight limits, spoils characterization (if uncertified fill is present, the material may require special handling or disposal), and coordination with the deputy inspector who must be on-site during hauling operations to count trucks and verify route compliance. Export quantities are determined by the approved civil plans - not estimated in the field.

Import operations - bringing certified fill onto the site for R&R or engineered fill placement - have the same logistical constraints in reverse, plus the additional requirement of material testing and certification before placement.

Removal and Recompaction (R&R)

When uncertified fill or inadequate bearing material is encountered, the typical response is removal and recompaction: excavate the unsuitable material, export what can't be reused, and place certified compacted fill in lifts with testing at each stage. On a hillside, R&R is complicated by limited staging area for excavated material, hauling constraints on narrow streets, the need for temporary shoring to maintain slope stability during excavation, and drainage management in the open excavation.

The soils engineer must observe and test every lift of replacement fill, typically at every 2 feet of placement. Nuclear density testing confirms compaction meets specifications. This is meticulous, sequential work that cannot be accelerated without compromising the foundation it supports.

Erosion Control and Stormwater

Open excavations on hillside sites are exposed to rain events in ways that flat lots are not. Water runs downhill - through your excavation, behind your shoring, into your neighbor's property, and onto the street below. A Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plan (SWPPP) is required for larger grading operations, and Best Management Practices (BMPs) must be installed and maintained throughout grading. Seasonal constraints are real: starting a hillside grading operation in October that won't be stabilized before the rainy season is a risk decision with significant cost implications if a storm event hits an open excavation.

Shoring and Foundations

On most hillside sites, the foundation system and the temporary shoring required to build it are the two largest cost items in the project - and they're deeply interdependent. The shoring sequence determines the excavation sequence, which determines the foundation construction sequence, which determines the structural steel and framing sequence above. Getting the shoring and foundation strategy right during pre-construction is the single most impactful decision on the project.

Why Shoring Is Almost Always Required

When you cut into a hillside, you remove the material that was holding the slope in place. The remaining soil above the cut needs to be retained - to protect adjacent properties, to protect streets and utilities above the excavation, and to meet OSHA excavation safety requirements. Shoring systems used in residential hillside construction include:

- Soldier pile and lagging: H-piles driven or drilled at regular spacing with timber lagging between them. The most common system for moderate depths and loads. Relatively fast to install and adaptable to varying conditions.

- Soldier pile with tiebacks: Same as above, but with grouted anchors extending into the retained soil behind the wall to resist higher lateral loads. Required for deeper excavations or when the retained slope carries surcharge loads (a neighbor's house, a street, a retaining wall above).

- Soil nail walls: Steel bars drilled into the slope face and grouted in place, with shotcrete facing. Can be faster than soldier pile systems in certain soil conditions and offers some flexibility in geometry.

- Pipe and board: For shallow, temporary support in tight-access conditions where larger equipment can't operate.

Tieback easements are a recurring issue on hillside projects. When tiebacks extend under a neighbor's property - which is common when excavating near a property boundary on a slope - a temporary or permanent easement must be negotiated with the adjacent property owner. When the neighbor says no, the design team must find alternatives: cantilevered walls, buttress fills, or redesigned excavation limits. This is a real estate and legal coordination issue that the CM must track alongside the technical one.

Foundation Systems

Hillside foundations are fundamentally different from flat-lot foundations because they must resist lateral loads from the slope in addition to the vertical gravity loads of the structure. The hill is pushing on your foundation. The foundation must resist both downward forces and sliding forces, often in seismic conditions that compound the lateral load problem.

Caissons (drilled shafts) with grade beams are the workhorse of LA hillside construction. Caissons are drilled into bedrock for bearing capacity and lateral resistance, and grade beams span between them to carry the structure. This system works because it can reach competent bearing material at variable depths across the site - each caisson goes as deep as it needs to, and the grade beams tie the system together structurally.

Other foundation systems used on hillside sites include soldier pile walls with structural grade beams, conventional footings where bearing soil is near the surface on relatively mild slopes, helical piers for tight-access conditions or supplemental support, and post-tensioned slabs on engineered pads with controlled fill. The system selection is driven by the geotechnical conditions and the structural loads - it's an engineering decision, not a preference.

Variable Bedrock: The Field Coordination Challenge

This is where hillside construction management separates from standard construction management. The geotechnical borings indicate bedrock at a certain depth. The structural engineer designs the foundation to bear at that depth. Then construction starts, and the actual bedrock is deeper - or shallower, or weathered rather than competent, or at a completely different elevation than the borings predicted 30 feet away.

When a grade beam is designed to bear on bedrock at one elevation and the field crew hits competent rock 3-4 feet lower, the grade beam needs to be deepened, which changes the rebar configuration, which changes the sliding force calculations, which may require additional pile resistance. The structural engineer and geotechnical engineer must coordinate a revised design while the drill rig is on site, rebar is being fabricated or delivered, and concrete is scheduled. Decisions that take weeks in design must be made in hours during construction.

The soils engineer must be on-site to observe and approve every caisson bottom before concrete is placed - confirming that the material at the bearing elevation is competent bedrock, not weathered rock or fill. This field verification is the moment where design assumptions meet reality, and the CM's role is to have the communication channels, the decision-making framework, and the schedule flexibility to handle whatever that moment reveals.

Drainage and Water Management

More hillside construction failures are caused by drainage problems than structural problems. Water follows gravity, and on a hillside, that means through your foundation, behind your retaining walls, under your building pad, and into your neighbor's property if it isn't managed at every level of the project.

Effective hillside drainage includes subdrain systems behind retaining walls (perforated pipe, drainage aggregate, filter fabric with outlets to the storm drain system), surface drainage above retaining walls (swales, area drains, terrace drains on cut slopes, V-ditches at the top of cuts), foundation perimeter drainage, and waterproofing systems for below-grade walls. Downspouts cannot discharge onto slopes - all roof drainage must be collected and conveyed to approved discharge points.

During construction, temporary drainage management is equally important. Open excavations on hillside sites must be protected from storm water intrusion. Dewatering systems may be required where groundwater is present. Erosion control BMPs must be maintained throughout the grading and foundation phase. The cost of proper drainage management during construction is a fraction of the cost of repairing slope failures, retaining wall damage, or foundation settlement caused by unmanaged water.

For projects that include standalone retaining walls - whether new construction, repair, or replacement - see Retaining Walls for wall types, drainage systems, construction methods, and the specific coordination requirements that apply to retention structures.

Retaining Walls

Retaining walls on hillside sites serve a different function than decorative landscape walls on flat lots. They're structural elements resisting thousands of pounds of lateral earth pressure, often supporting slopes that carry streets, utilities, or neighboring structures above them. The design, construction, and long-term performance of retaining walls is one of the most consequential decisions on any hillside project - and one of the most common sources of failure when done incorrectly.

Types of Retaining Walls

Retaining wall selection depends on the height of retention, the soil conditions, the loads being retained (just soil, or soil plus a driveway, or soil plus a neighbor's house), available space for the wall footprint, and access for construction equipment. The main types used in Los Angeles hillside residential construction:

| Wall Type | How It Works | Typical Application | Height Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravity walls | Mass of wall resists overturning. No steel reinforcement. Stone, concrete block, or mass concrete. | Low walls, landscape applications, minimal surcharge | Up to 4 feet |

| Cantilever walls | Reinforced concrete stem and footing. The weight of soil on the heel helps resist overturning. | Most common structural retaining wall. Moderate heights, adequate bearing soil. | 4-20 feet |

| Counterfort walls | Cantilever wall with vertical ribs (counterforts) on the backfill side for additional strength. | Taller walls where cantilever stem thickness becomes impractical | 15-30+ feet |

| Soldier pile walls | Steel H-piles drilled into bedrock with concrete or timber lagging between. May include tiebacks. | Deep cuts, poor bearing soil, temporary or permanent retention near property lines | 10-40+ feet |

| Soil nail walls | Steel bars drilled and grouted into existing slope face, with shotcrete facing. | Stabilizing existing slopes, cuts where conventional wall footings aren't feasible | 10-50+ feet |

| MSE walls (Mechanically Stabilized Earth) | Segmental facing units with geogrid reinforcement extending into compacted backfill. | Highway applications, large fills. Less common in residential due to space requirements. | 10-40+ feet |

| Caisson walls | Drilled shafts (caissons) with structural grade beam spanning between them. Often combined with soldier pile lagging above. | High loads, deep bedrock, combines foundation and retention functions | 15-40+ feet |

Retaining Walls Are Part of a Hillside Stability System

On hillside sites, a retaining wall is rarely an isolated element. Wall performance depends on global slope stability, groundwater behavior, surface drainage, utility corridors, and surcharges from adjacent improvements. A wall can be built exactly per plan and still experience distress if site conditions - water, loading, or soil behavior - differ from the assumptions used in design.

The distinction matters: wall failure is when the wall itself is inadequate for the loads it's retaining. Slope failure is when the hillside moves and takes the wall with it. A code-compliant wall on an unstable slope will still fail. One wet winter can reset the groundwater regime and trigger movement that wasn't predicted by a geotech report done during a drought year.

Property Line Constraints and Tieback Realities

Many retaining walls over 10-12 feet require tiebacks or soil nails to resist overturning. On tight hillside lots, the anchor zone often extends beyond the wall footprint - which means it crosses property lines or conflicts with utilities. This is frequently the gating constraint that determines wall type, cost, and schedule.

- Tieback easements: If anchors extend under neighboring parcels, a recorded easement is typically required. Without rights, the design must change - often to a more expensive cantilevered or buttressed system that doesn't need anchors.

- Neighbor coordination: Getting easement rights requires neighbor cooperation. A neighbor who says no - or who wants compensation - can fundamentally change the project scope and budget.

- Utility conflicts: Existing and proposed utilities can block anchor alignments or limit drilling angles. Sewer lines, gas mains, and electrical conduits don't move for your tiebacks. Early potholing and utility mapping prevents redesigns mid-construction.

- Survey control: Walls near property lines require precise layout and monitoring to prevent encroachment. A wall that's 6 inches over the line is a legal problem, not just a construction problem.

What Retaining Walls Must Resist

Understanding the forces on a retaining wall explains why they're engineered structures, not just concrete in the ground. A retaining wall must resist:

- Lateral earth pressure: The horizontal force exerted by retained soil. Increases with wall height - doubling the height more than doubles the overturning moment. Varies significantly based on soil type (clay vs. sand vs. rock) and moisture content.

- Surcharge loads: Additional loads on the retained soil surface - a driveway, a parked car, a swimming pool, an adjacent structure. Surcharge loads can double or triple the lateral force on the wall.

- Hydrostatic pressure: Water pressure behind the wall if drainage fails. Water weighs 62.4 pounds per cubic foot. A 10-foot wall with saturated backfill and no drainage has over 3,000 pounds per linear foot of additional lateral force that the wall wasn't designed for. This is why drainage is not optional.

- Seismic loads: During an earthquake, lateral earth pressure increases significantly (the Mononobe-Okabe method is used to calculate seismic earth pressure in LA). California seismic design requirements are among the most stringent in the country.

- Sliding resistance: The wall must not slide forward on its footing. Dependent on friction between footing and bearing soil, plus any passive resistance from soil in front of the toe.

- Bearing capacity: The footing must not exceed the bearing capacity of the underlying soil, or the wall settles and rotates.

Drainage: The Most Critical Detail

More retaining walls fail from drainage problems than from structural inadequacy. When water accumulates behind a retaining wall, three things happen: hydrostatic pressure adds lateral load the wall wasn't designed for, saturated soil is heavier and exerts more pressure, and water migration can erode bearing soil under the footing. The wall that stood fine for 20 years fails after one wet winter because the drainage system clogged.

Proper retaining wall drainage includes:

- Drainage aggregate: Free-draining gravel (typically Class 2 permeable) behind the wall, minimum 12 inches wide, full height of wall.

- Filter fabric: Geotextile fabric separating drainage aggregate from retained soil to prevent fines migration and clogging.

- Perforated subdrain pipe (french drain): At the base of the drainage aggregate, sloped to outlet. Minimum 4-inch diameter, typically 6-inch on larger walls.

- Outlets: Subdrain must discharge to an approved location - storm drain, daylight to slope face below wall, or sump with pump. Outlets must remain clear and functional for the life of the wall.

- Weep holes: Secondary drainage through the wall face, typically 4-inch PVC at regular spacing, as backup if subdrain capacity is exceeded.

- Surface drainage: Swales, area drains, or other systems to prevent surface water from entering the backfill zone above the wall.

Shotcrete vs. Poured-in-Place Concrete

Most residential retaining walls in Los Angeles are built one of two ways: poured-in-place concrete using traditional formwork, or shotcrete (pneumatically applied concrete) sprayed against rebar and either the retained earth or a temporary form. The choice affects cost, schedule, finish options, and what geometries are feasible.

Shotcrete retaining walls eliminate or reduce formwork on the retained side - the concrete is sprayed directly against the excavated face or a simple backing. This typically saves 20-30% on labor and materials compared to fully formed poured walls of equivalent height. Shotcrete also handles curved walls easily - the nozzle follows any geometry, while curved formwork for poured concrete is expensive custom work.

The trade-offs with shotcrete include rebound - material that bounces off during application, typically 5-15% waste that must be removed from the site. Shotcrete also requires skilled nozzlemen; poor application technique creates voids, laminations, and inconsistent concrete quality. The exposed face requires finishing work after application - screeding to grade using piano wire guides, then floating or troweling to the specified texture.

Poured-in-place concrete is the conventional approach: build forms on both faces, place rebar, pour concrete, strip forms. It produces more precise dimensions, better control over wall thickness, and cleaner geometry at corners and terminations. For walls adjacent to habitable space or where water-tightness is critical, poured concrete typically performs better because the forming process produces denser, more consistent concrete.

| Factor | Shotcrete | Poured-in-Place |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | 20-30% lower | Baseline |

| Curved walls | Easy - nozzle follows any geometry | Expensive custom formwork |

| Finish quality | Requires post-application finishing | Form finish (smooth, board-form, etc.) |

| Dimensional precision | Variable - depends on nozzleman skill | Precise - controlled by formwork |

| Water-tightness | Good with proper application | Better - denser, more consistent |

| Waste | 5-15% rebound | Minimal |

| Best application | Utilitarian walls, soil nail facing, curved geometry, cost-sensitive projects | Architectural walls, adjacent to habitable space, board-form finish |

Finish and Architectural Integration

On residential projects, retaining walls are often visible - from the house, from outdoor living areas, from the street. The structural requirements don't change, but the finish and detailing become design decisions that affect both cost and the architect's intent.

Concrete finishes range from utilitarian to architectural:

- Gun finish (shotcrete): The natural texture from shotcrete application - rough, irregular, typically used where the wall will be covered or isn't visible. Lowest cost.

- Float finish: Shotcrete or poured concrete worked with a wood or magnesium float to a uniform but textured surface. Mid-range appearance, common for landscape walls.

- Steel trowel finish: Smooth, dense surface achieved by troweling. Works for both shotcrete and poured concrete, though easier to achieve consistency with formed walls.

- Board-form finish: Wood grain texture transferred from the formwork. Requires poured-in-place concrete with carefully selected and sealed form boards. High-end architectural finish with significant cost premium.

- Reveals and patterns: Horizontal or vertical grooves created by form inserts. Common on modern residential projects. Must be detailed on structural drawings and coordinated with rebar placement.

Veneer and cladding can transform a structural concrete wall into something else entirely - natural stone, manufactured stone, tile, stucco. The structural wall is designed the same way; the veneer is an architectural finish applied after the wall is built. Key considerations include anchorage (veneer systems require embedded anchors or adhesive systems rated for the weight and exposure), waterproofing behind the veneer (water that gets behind stone veneer and freezes will destroy it), and maintenance access (if the veneer fails in 20 years, can it be repaired without excavating the backfill?).

Guardrails and safety are code requirements when there's a drop on the other side of the wall. Walls over 30 inches high with accessible areas at the top require 42-inch guards. The guardrail attachment must be designed by the structural engineer - posts anchored into the wall cap or face, with connections that can resist the code-required loading. This isn't an afterthought; it's detailed during wall design.

Integrated elements that architects often incorporate into retaining walls include built-in planters (require waterproofing, drainage, and irrigation rough-in), lighting (conduit and junction boxes cast into the wall or surface-mounted after), seating (cap width and height designed for sitting), and water features (waterproofing, plumbing, and equipment access all coordinated before the wall is built).

Waterproofing and Buried Interface Details

Drainage relieves hydrostatic pressure, but waterproofing protects the wall and adjacent improvements from water migration. On residential projects where the wall is adjacent to habitable space, finish materials, or foundations, water intrusion through or around the wall causes damage that's expensive to remediate after the fact.

- Dampproofing vs. waterproofing: Not interchangeable. Dampproofing resists moisture vapor. Waterproofing resists liquid water under pressure. The specification depends on water exposure and adjacencies - a wall retaining soil next to a basement requires waterproofing, not just dampproofing.

- Protection board and drainage mat: Protects the membrane during backfill (angular aggregate can puncture membranes) and improves vertical drainage performance behind the wall.

- Cold joints and penetrations: The most common leak paths. Construction joints, keyways, weep hole sleeves, and utility penetrations are all weak points that require specific detailing - waterstops, sealants, or membrane boots depending on the system.

- Top-of-wall detailing: Cap flashing and surface drainage above the wall prevent water from entering the backfill zone from above. A wall with perfect subdrain but no cap control still gets water behind it every time it rains.

Construction Sequence

Retaining wall construction on hillside sites follows a specific sequence driven by safety and structural requirements:

Each inspection point is a potential hold if conditions don't match the design. Bearing soil that doesn't meet the assumed capacity requires footing redesign or ground improvement. Rebar placement that doesn't match the structural drawings requires correction before concrete. Drainage that isn't installed per plan requires removal and reinstallation before backfill.

Inspection and Test Plan

Retaining walls include critical buried conditions that cannot be verified after backfill. A disciplined inspection and test plan protects the owner by documenting every element before it's concealed. This is the difference between hoping the wall was built right and knowing it was.

Each hold point is documented with photos, test reports, and inspection records. This documentation serves two purposes: it confirms the work was done correctly during construction, and it provides evidence if questions arise years later about how the wall was built.

Permitting Requirements

Retaining walls over 4 feet in height (measured from bottom of footing to top of wall) require a building permit in the City of Los Angeles. What's included in the permit package:

- Structural drawings: Prepared by a licensed civil or structural engineer. Wall geometry, reinforcement, footing design, drainage details.

- Geotechnical report: Soil conditions, bearing capacity, lateral earth pressure coefficients, drainage recommendations. Must be project-specific, not a generic report from a prior owner.

- Grading plan: If wall construction involves more than 50 cubic yards of cut or fill, or if on a slope steeper than 5:1, a grading permit is required in addition to the building permit.

- Survey: Property boundaries, existing grades, proposed wall location. Critical when wall is near property lines.

Walls within Hillside Areas are subject to BHO grading limits - the excavation for the wall footing counts against your Maximum Grading Quantities. In HCR districts, hauling restrictions apply to any export from wall excavation. These regulatory constraints are the same as for any other hillside construction and must be factored into the project plan.

Common Failure Modes

Understanding how retaining walls fail helps understand why proper design, construction, and inspection matter:

- Wall rotates outward at the base

- Caused by lateral load exceeding design

- Often triggered by drainage failure or unanticipated surcharge

- Progressive - gets worse once it starts

- Wall moves horizontally at the footing

- Friction and passive resistance exceeded

- Can be sudden if bearing soil is saturated

- Common when key or shear key is omitted

- Footing sinks into inadequate soil

- Wall tilts and cracks as it settles unevenly

- Caused by bearing on fill, expansive clay, or soft material

- Should be prevented by geotech verification at excavation

- Wall stem cracks and breaks under bending

- Inadequate reinforcement for actual loads

- Corrosion of rebar due to inadequate cover

- Should never happen if designed and built to code

The first three failure modes - overturning, sliding, and bearing - are geotechnical failures that occur when actual conditions don't match design assumptions, or when conditions change after construction (drainage failure, new loads added). Stem failure is a structural failure from inadequate design or construction defects. All are preventable with proper engineering, construction quality control, and inspection.

Retaining Wall Repair and Remediation

Existing retaining walls that show signs of distress - cracking, tilting, bulging, settlement - require evaluation before any repair decision. The symptoms are visible; the cause is often not. A wall that's rotating outward could be failing due to drainage problems, new surcharge loads, bearing failure, or original design inadequacy. The repair approach depends on the cause.

Common remediation approaches include:

- Drainage rehabilitation: If failure is drainage-related and the wall is structurally adequate, installing new drainage behind the wall (requires excavation) may stabilize it.

- Tieback installation: Drilling anchors through the existing wall into competent material behind to add resistance. Can be effective for overturning if bearing and stem are adequate.

- Underpinning: If bearing is inadequate, extending the footing depth or adding helical piers to reach competent material.

- Partial or complete replacement: When the wall is too far gone or the original design was fundamentally inadequate, demolition and reconstruction may be the only viable path.

Fire-Damaged Retaining Walls

Wildfires create unique damage patterns in concrete retaining walls that differ from normal aging or structural failure. After the Palisades and Eaton fires, thousands of homeowners are discovering retaining walls that look intact but may have suffered hidden damage that compromises their structural capacity and drainage systems.

How Fire Damages Concrete

Concrete doesn't burn, but it degrades significantly at high temperatures. The damage depends on how hot the fire burned and for how long:

- Surface discoloration (300-600°F): Concrete turns pink or red when heated above 500°F - a visible indicator that the material reached temperatures where strength loss begins. This discoloration is often the first sign of thermal damage.

- Strength reduction (600-1,200°F): Concrete loses 25-50% of its compressive strength in this range. The wall may look intact but no longer has the capacity it was designed for.

- Explosive spalling: Moisture trapped in concrete flashes to steam under intense heat, causing chunks of surface concrete to blow off. This exposes reinforcing steel and reduces the effective wall thickness.

- Rebar exposure and damage: Once cover concrete spalls off, rebar is exposed to direct flame and begins losing strength above 750°F. Exposed rebar also becomes vulnerable to corrosion, accelerating long-term deterioration.

- Thermal cracking: Rapid heating and cooling creates crack patterns different from settlement or overturning - often a network of fine cracks across the fire-exposed face.

Evaluation Process

Fire-damaged retaining walls require systematic evaluation before any repair-or-replace decision:

- Visual inspection: Document discoloration patterns, spalling, exposed rebar, cracking, and any displacement or tilting. Photograph everything before any cleanup or debris removal.

- Hammer sounding: Tap the wall surface with a hammer - solid concrete sounds sharp, damaged concrete sounds hollow or dull. This helps map the extent of subsurface damage.

- Core sampling: If strength is in question, a testing lab can core the wall and test compressive strength of the damaged concrete versus the design strength.

- Drainage system assessment: This typically requires exploratory excavation behind the wall to inspect subdrain pipes, filter fabric, and drainage aggregate. Assume the drainage is compromised until proven otherwise.

- Structural engineer evaluation: A licensed structural engineer should assess whether the wall's remaining capacity is adequate for the loads it's retaining, especially if rebar is exposed or significant spalling has occurred.

Repair vs. Replacement

The repair-or-replace decision depends on the extent of damage and the cost-benefit of each approach:

- Damage is limited to surface discoloration and minor spalling

- Rebar remains covered or exposure is minimal

- Core tests confirm adequate residual strength

- Drainage system is intact or accessible for rehabilitation

- Wall geometry (plumb, alignment) is unchanged

- Extensive spalling with widespread rebar exposure

- Core tests show significant strength loss

- Wall has moved, tilted, or cracked through

- Drainage system is destroyed and wall access is difficult

- Repair cost approaches or exceeds replacement cost

Repair options for salvageable walls include surface preparation and patching with polymer-modified repair mortar, rebar treatment or supplemental reinforcement where steel is exposed, shotcrete overlay to restore section thickness and protect rebar, and drainage rehabilitation (excavation and new subdrain installation).

Insurance Documentation

Before any demolition, cleanup, or repair work begins, document everything for your insurance claim:

- Photographs: Overall wall condition, close-ups of damage (spalling, cracks, discoloration), any displacement or tilting, drainage outlets, and the relationship to the burned structure.

- Video walkthrough: Narrated video documenting the full extent of damage provides context that photos alone may not capture.

- Professional reports: Structural engineer assessment, geotechnical evaluation if slope stability is in question, and drainage system inspection report.

- Historical documentation: If available, original permits, engineering drawings, and any prior inspection reports establish what existed before the fire.

- Cost estimates: Get written estimates for both repair and replacement options from qualified contractors before making a claim decision.

Preconstruction Decisions That Reduce Cost and Risk

The biggest cost savings on retaining walls happen before construction starts - during design and preconstruction when decisions are still flexible. By the time you're pouring concrete, the expensive choices have already been made.

- Reduce wall height through grading: A few feet of grade adjustment can eliminate tiebacks, reduce stem thickness, and shrink footing size. Moving dirt is often cheaper than engineering around it.

- Terrace instead of one tall wall: Two 8-foot walls often outperform one 16-foot wall in cost, constructability, and drainage. Each wall is simpler, and the bench between them provides maintenance access and drainage control.

- Plan access before design is finalized: Drill rig access, spoils handling, and concrete placement strategy can dictate what's feasible. A wall that's elegant on paper but requires a spider crane and hand-placed concrete costs twice what a buildable design costs.

- Quantify earthwork early: Export, import, and trucking constraints are often bigger schedule drivers than the wall itself. In HCR districts, the hauling window may control your entire grading timeline.

- Confirm tieback rights before finalizing wall type: If you design a tieback wall and then discover the neighbor won't grant an easement, you're redesigning from scratch.

- Choose shotcrete vs. poured based on finish requirements: If the wall will be covered or isn't architecturally prominent, shotcrete can save 20-30%. If you need board-form finish, that decision drives the construction method.

Cost Considerations

Retaining wall costs vary dramatically based on wall type, height, length, site access, and soil conditions. General ranges for Los Angeles hillside residential:

| Wall Type | Cost Range (per linear foot) | Key Cost Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Gravity/landscape walls (under 4') | $150-400 | Materials, site access, finish treatment |

| Cantilever walls (4-10') | $400-800 | Height, bearing conditions, reinforcement, drainage |

| Cantilever walls (10-20') | $800-1,500 | Footing size, form complexity, equipment access |

| Shotcrete walls (any height) | 20-30% less than formed equivalent | Nozzleman skill, rebound disposal, finish requirements |

| Soldier pile walls | $1,000-2,500 | Pile depth, spacing, tieback requirements, lagging type |

| Soldier pile with tiebacks | $1,500-3,500 | Number of tieback rows, anchor length, easement requirements |

| Caisson walls | $2,000-5,000+ | Caisson depth, diameter, grade beam complexity |

These are construction costs only. Add engineering (typically $15K-50K for structural and geotech on significant walls), permitting, and inspection. Site access constraints can add 30-50% to construction costs on hillside sites where equipment mobilization is difficult.

Retaining Wall FAQs

In Los Angeles, walls over 4 feet (measured from bottom of footing to top of wall) require a building permit. Walls in Hillside Areas may trigger additional grading permits and BHO compliance review regardless of height.

Cracking can be shrinkage (cosmetic, non-structural) or movement-related (structural). Horizontal cracks, stair-step patterns, or cracks that widen over time indicate potential structural issues. A structural engineer should evaluate before assuming it's cosmetic.

Maybe - but surcharge loads dramatically increase lateral pressure on the wall. The existing wall must be evaluated by a structural engineer before adding loads it wasn't designed for. Reinforcement or replacement may be required.

Tieback anchors extend into the ground behind the wall - often 20-40 feet. On properties near the boundary, anchors cross under the neighbor's land. You need a recorded easement for permanent encroachment, or you redesign without tiebacks.

Drainage system degradation. Clogged outlets, collapsed pipes, missing filter fabric, or poor surface drainage cause failures years after construction. A wall that stood for 20 years can fail after one wet winter if the drainage stops working.

A properly designed, constructed, and maintained retaining wall should last 50+ years. The variables are drainage performance, rebar corrosion (dependent on concrete cover and quality), and whether loads or conditions change over time.

Tilting or leaning outward, horizontal cracking (especially near the base), stair-step cracks following mortar joints, bulging in the middle of the wall, settlement or separation at the top, and water staining or efflorescence on the wall face. Any of these warrant professional evaluation.

Neither is inherently better - it depends on the application. Shotcrete is 20-30% cheaper and handles curves easily, but poured concrete produces better architectural finishes and more precise dimensions. The choice should match your finish requirements and budget.

Repair costs range from $10K-50K for drainage rehabilitation or tieback installation to $50K-500K+ for partial or complete replacement. The cost depends on wall size, site access, cause of failure, and whether the wall supports critical loads. Evaluation by a structural engineer is the first step.

Potentially. Unpermitted walls may not meet code, may not have been engineered for actual loads, and may not have proper drainage. They can also create issues when selling or refinancing. A structural engineer can evaluate the wall's adequacy; permitting after the fact may be possible but often requires demonstrating code compliance.

The Construction Manager's Role

On retaining wall projects, the CM coordinates between the geotechnical engineer, structural engineer, and contractor to ensure what gets built matches what was designed - and that field conditions confirm design assumptions. Specific CM responsibilities include:

- Pre-construction: Reviewing wall design for constructability, verifying equipment access, confirming tieback rights and utility clearances, coordinating survey and layout, and identifying potential conflicts before they become field problems.

- During excavation: Ensuring soils engineer is present to verify bearing conditions before footing concrete. If bearing doesn't match assumptions, coordinating redesign before proceeding.

- During construction: Managing the inspection and test plan - verifying rebar placement, witnessing waterproofing and drainage installation, confirming compaction testing during backfill. Every buried element documented before it's covered.

- Documentation: Photo documentation of all buried elements, compaction test reports, inspection records, as-built drawings showing actual drain outlet locations. This documentation matters if questions arise years later.

The Cost and Schedule Reality

The question architects and homeowners ask most frequently about hillside construction is "how much more does it cost?" The answer is that hillside sites don't carry a simple percentage premium over flat-lot construction - the premium is concentrated in specific categories, and understanding where the money goes is essential to setting realistic budgets and making informed design decisions.

What Drives Hillside Construction Cost

| Cost Category | What It Includes | Typical Premium Over Flat-Lot |

|---|---|---|

| Site access and logistics | Equipment mobilization constraints, spider cranes, limited-access rigs, material delivery coordination, constrained staging | 2-5x equipment costs |

| Geotechnical and foundations | Additional borings, caissons/piles to bedrock (30-60+ feet vs. 3-foot spread footings), grade beams, soils engineer observation at every bearing point | 5-15x foundation costs |

| Shoring and retention | Soldier piles, tiebacks, retaining walls, subdrain systems, tieback easement coordination | Often $200K-$1M+ (may not exist on flat lot) |

| Grading and earthwork | Cut/fill operations, export hauling, R&R if uncertified fill is discovered, haul route compliance, deputy inspector | 3-10x per cubic yard |

| Coordination | More consultants (geotech, structural, civil, shoring designer), more inspections, more plan check cycles, more agency coordination | 2-3x soft costs |

| Risk/contingency | Higher probability of field conditions diverging from design, weather sensitivity, neighbor issues | 15-25% contingency vs. 10% on flat lot |

Flat Lot, Westside

Hillside Lot*

*Range varies significantly based on site access, foundation complexity, and finish level. High-end luxury finishes can push costs higher.

The premium is almost entirely in site work, foundations, and the coordination required to manage the complexity. The house itself - framing, mechanical/electrical/plumbing, finishes - costs roughly the same whether it sits on a flat lot or a hillside. It's everything below the first floor that drives the differential.

Schedule Reality

| Phase | Hillside | Flat Lot |

|---|---|---|

| Permitting | 6-18 months | 3-6 months |

| Site development | 4-12 months | 1-3 months |

| Structure and finishes | 12-18 months | 10-14 months |

| Total project | 18-36+ months | 12-18 months |

The schedule difference is concentrated in permitting and site development. Multi-agency permitting with dependencies, restricted grading and hauling windows, complex foundation systems requiring field verification, and the sequential nature of hillside construction (shoring must be complete before foundation, foundation before structure - there's less ability to overlap phases than on flat sites) all extend the timeline.

Extended schedule has a direct cost impact beyond the obvious. Every additional month is another month of general conditions (supervision, insurance, temporary facilities, equipment rental), another month of exposure to weather events, and another month of opportunity for field conditions to change. This is the schedule-cost spiral, and it's why pre-construction planning matters more on hillside sites than anywhere else. See Feasibility Report for how this planning is structured.

The Construction Manager's Role on Hillside Projects

The construction manager's role on a hillside project is fundamentally different from its role on a flat-lot build - not in kind, but in intensity. Every function a CM performs on any project (constructability review, budget development, subcontractor coordination, schedule management, field oversight) is amplified by the complexity of hillside conditions. The margin for error is smaller, the decision-making pace is faster, and the cost of getting it wrong is higher.

Pre-Construction

Pre-construction on a hillside project is where the CM delivers the most value relative to cost. This phase includes:

- Geotechnical scope review: Evaluating whether the investigation scope matches the site complexity, and recommending additional borings when the construction risk of insufficient data exceeds the investigation cost.

- Constructability review: Reviewing structural and civil plans for buildability - can the designed foundation actually be constructed with available equipment on this site? Are the assumed bearing elevations realistic given the geotech data? Does the grading plan comply with BHO/HCR limits?

- Equipment access and logistics planning: Determining what equipment fits the site, planning crane pad requirements, identifying staging areas, and developing the delivery coordination strategy.

- Shoring and excavation sequence: Working with the shoring designer to develop a sequence that maintains slope stability while creating efficient access for foundation construction.

- Budget development with hillside-specific categories: Building cost estimates that account for access premiums, foundation complexity, grading constraints, extended schedule, and appropriate contingency for field condition risk.

- Agency coordination and permit strategy: Mapping the multi-agency permitting path, identifying dependencies, and enabling parallel processing where possible.

- Subcontractor prequalification: Identifying drilling contractors, grading contractors, and shoring contractors who have experience on hillside residential sites in Los Angeles - not just licensed, but experienced with the specific constraints these projects present.

During Construction

During construction, the CM's role shifts to real-time coordination and decision management. On a hillside project, this means:

- Field verification at critical milestones: Being present when caissons reach bearing, when shoring is loaded, when excavations expose actual soil conditions. These are the moments when design assumptions are confirmed or revised.

- Soils engineer coordination: Managing the schedule interface between the soils engineer's observation requirements and the construction sequence. On a hillside foundation, the soils engineer may need to approve 20+ individual caisson bottoms - each one a potential hold point if conditions don't match the design.

- Real-time communication: Maintaining open channels between the structural engineer, geotechnical engineer, and field crew so that when conditions diverge from design, the information reaches the right people immediately and decisions are made with complete information.

- Decision framework when conditions don't match design: Document the condition, notify the design team with clear information, propose constructable solutions, get direction before proceeding, and track cost and schedule impact. This cycle may repeat multiple times per week on a complex hillside foundation.

This page provides general information about hillside construction in Los Angeles and is not intended as geotechnical, structural, or legal advice. Specific projects require evaluation by licensed professionals. Regulatory information reflects conditions as of February 2026; ordinances and requirements are subject to change. Consult LADBS and LA City Planning for current requirements applicable to your property.